Hamed Vafaei – Professor of China Studies, University of Tehran

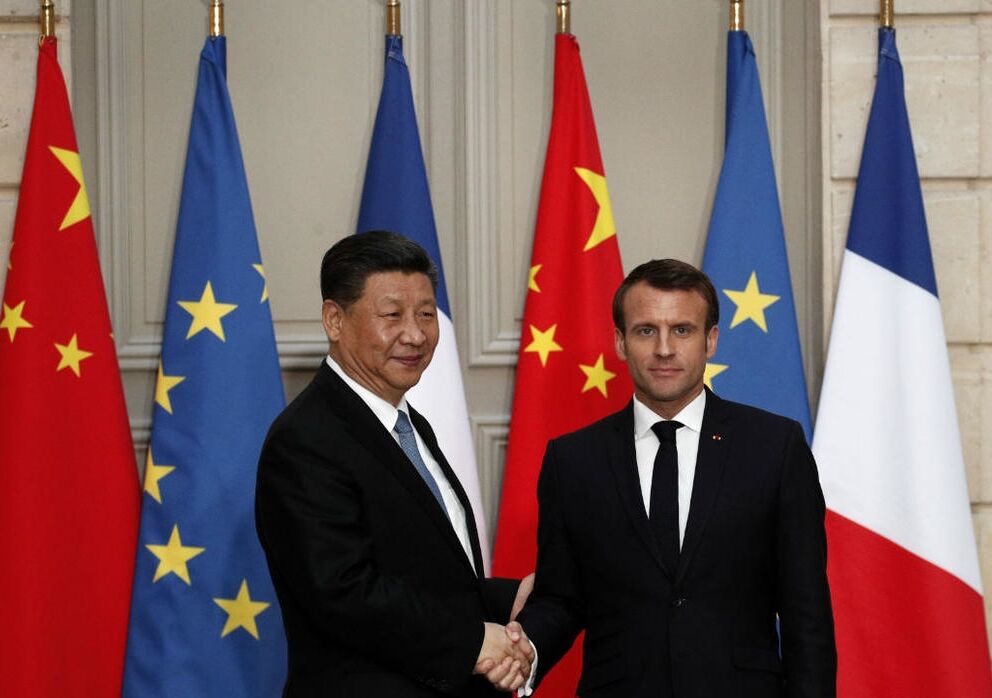

The recent wave of visits by Western (especially European) officials to Beijing – Emmanuel Macron (December 2025), Micheál Martin (Ireland, January 2026), Keir Starmer (United Kingdom, January 2026), Petteri Orpo (Finland, January 2026), and the planned upcoming visit of Friedrich Merz (Germany, February 2026) – can largely be interpreted as a tactical reaction to Trump’s recent actions toward Europe rather than a sustainable strategic shift in these countries’ perceptions of China.

Regarding the current atmosphere of Europe–China relations, it can be stated that with the return of Trump’s aggressive policy, including the imposition of extensive tariffs, the threat of 100 percent tariffs against Canada and the United Kingdom should these countries reach agreements with China, as well as pressure on Europe for complete security-economic alignment with the United States, many European governments have concluded that their excessive dependence on the United States has turned into a strategic risk for them.

On the other hand, it appears that the European Union, following the relative failure of its efforts to strengthen its relations with Beijing in 2025, particularly after China tightened restrictions on the export of rare mineral elements in the autumn of 2025, has now inclined toward a risk-management strategy while maintaining open channels for engagement.

In such an environment, China, as the primary target of the United States’ aggressive policy, has precisely capitalized on this vulnerability of the European parties and, by inviting European leaders and accompanying their large trade delegations, simultaneously conveys two messages to Washington and European capitals: first, it signals to the United States that in the event of a worsening trade and technology war with Washington, Beijing possesses the capability to provide substitution in certain significant areas by leveraging Europe’s capacity; and it warns Europe that if they enter into a bilateral trade war with Washington, China can be a reliable partner to compensate for potential gaps they may face.

Beijing’s Strategic Outlook toward the European Union

Under such conditions, examining Beijing’s strategic outlook toward the European Union also appears necessary; from the perspective of Xi Jinping, the leader of China, and the country’s diplomatic apparatus, the European Union possesses three key characteristics:

- It is the largest consumer market in the world after China, providing a vital capacity to compensate for the saturation of China’s domestic market in the event of reduced exports to the United States.

- It is one of the poles of global technology and standard-setting, particularly in the fields of green energy, digital technologies, and electric vehicles, where China still requires European standards in certain value chains related to these sectors.

- It is the weakest link in the Western alliance chain, meaning that not only does it lack a unified army, but it also suffers from the absence of unified political will and possesses deep divides in the North–South and East–West domains.

Accordingly, Beijing’s strategy toward Europe has always been a combination of hard and soft strategies. While offering major trade incentives to pragmatic European countries, including Spain, Italy, Ireland, Hungary, and Serbia, Beijing has exerted a form of targeted and fully managed pressure on countries such as Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Sweden, and, to some extent, Germany and France.

As recent positions of Chinese officials indicate, Beijing in 2026 is intensifying this strategy and seeks to divide Europe into three distinct camps:

– The pragmatic and trade-oriented camp (Ireland, Spain, Italy, Austria, Hungary)

– The hesitant and balancing camp (Germany, France, the Netherlands)

– The value-oriented and security camp (the Baltic states, Poland, and to some extent the Scandinavian countries)

In the meantime, it appears that the European Union continues to analyze China as an actor characterized by three features: partnership, competition, and systemic rivalry. The concept of partnership includes climate issues, renewable energy, and certain supply chains, including those for batteries and solar panels. Its competitive domains are concentrated in green industries, electric vehicles, and digital technologies. The concept of systemic rivalry largely refers to Beijing’s indirect support for Moscow in the Ukraine war, control over the export of strategic items, and influence over Europe’s critical infrastructure, in the context of competition and major-power equations in the international system.

However, since late 2025, and particularly after the intensification of Trump’s trade war, it appears that the prioritization of European countries, even if at tactical levels, has changed, based on which these countries lack the capacity to confront both the United States and China simultaneously; therefore, many European capitals now believe that a bilateral trade war with Beijing, concurrent with the escalation of ongoing tensions with Washington, would in practice be unbearable for Europe’s fragile economy. For this reason, even previously hardline figures such as von der Leyen adopted a milder tone regarding China at the 2026 Davos meeting and even spoke of the possibility of “expanding trade and investment with Beijing.”

Regarding the future of China–European Union relations, three scenarios are conceivable: a managed and volatile engagement scenario; a pessimistic scenario involving escalation of bilateral tensions with China simultaneously with U.S. pressures; and finally an optimistic scenario involving the possibility of reaching a minimal agreement with both sides.

Accordingly, if the current situation continues, Europe’s trade with China will persist at high levels, but will face increasing obstacles. Regular high-level dialogues between the two sides will, of course, continue without noticeable progress, and the instrumental use of China by Europeans to counter U.S. pressure will remain on the agenda.

In this context, the first scenario is based on the principle that relations between the parties will neither warm nor reach a complete rupture; however, in the second scenario, should Beijing intensify the use of the rare mineral restriction tool in its interactions with Europe or make its support for Russia more explicit, while Trump simultaneously imposes heavy tariffs on European goods, Europe will be compelled to make a difficult choice, which will likely entail a greater inclination toward Washington at the cost of losing European values and bearing other heavy costs, including economic recession and inflation in the energy sector.

In the third scenario, which encompasses a more optimistic environment, achieving a temporary agreement in the fields of rare minerals, electric vehicles, and certain green standards, accompanied by a reduction of tensions in Ukraine, will be placed on the agenda, allowing Beijing to play the role of a “responsible mediator” in these international equations. The realization of this scenario naturally requires considerable flexibility from both sides, which, given Washington’s radical performance in all domains, especially during the Trump era, does not appear highly probable.

Overall, it appears that China–EU relations in 2026–2027 can be likened to “cautious relations between two trade partners in pre-crisis conditions,” rather than a strategic alliance or an all-out confrontation.

Today, although Europe needs China to mitigate Washington’s blows, it still does not trust Beijing; on the other hand, China also needs Europe to prevent further isolation vis-à-vis the United States, yet it does not practically perceive within itself the will to change its behavior to meet European expectations fully. The result of this contradiction is the formation of relations filled with controlled tensions, short-term tactical agreements, and continuous efforts to preserve diverse options; an environment that Beijing has termed “orderly and equal multipolarity,” and that Brussels refers to as a “risk-balancing strategy.”

This text was translated using artificial intelligence and may contain errors. If you notice a clear error that makes the text incomprehensible, please inform the website editors.

0 Comments